Learning Linux/Unix

Research ComputingJohn Wallace john.m.wallace@dartmouth.edu

UNIX is simple and coherent, but it takes a genius (or at any rate a programmer) to understand and appreciate the simplicity.- Dennis Ritchie

Research Computing

The Research Computing group provides consulting, hardware, software and systems to help researchers:- Programming, Statistics, database, systems and tools support

- Storage (RSTOR/AFS) - available to desktop as well as central systems

- Research systems Andes, Polaris, RCGPU,Discovery, web server Share, distribute data (caligari) and off site access (sshlogin)

- New initiatives:

- RCGPU 500+ cpu's in one machine

- CoLab, Virtual machines, publishing support, Media Thread, GIS data server

Goals

- "Learn a little bit about Linux/UNIX"

- "Login" = connect to a remote computer

- Use the basic UNIX commands to create files and directories

- Understand the UNIX tools philosophy --- Information/data Legos

- Find online help

- Learn to explore

Why Learn Linux/UNIX?

- Appreciate Linux/UNIX humor ...

If you have any trouble sounding condescending, find a Unix user to show you how it's done. --- Scott Adams

- Peek under the hood, It's fun to understand how things work

- Internet was built on UNIX and "open source" / "free software"

- Mac is UNIX/Linux

- More powerful tools than graphical user interfaces (GUI)

wget --mirror -p --convert-links -P ./dartmouthwww www.dartmouth.edu - The test of time .... History (UNiplexed Information and Computing Service)

History of Unix 1

- UNIX was "created" 1969. UNIX time is kept from Jan 1, 1970.

- Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie (AT&T Bell Labs), Multics, PDP7, PDP11. The PDP11 was a 16-bit machine, so programs were restricted to 64kB, and this encouraged modular programming and cooperating processes.

- Dennis Ritchie wrote "C", a descendant of "B" and "BCPL". Thompson and Ritchie rewrote the Unix kernel in "C" (1973) - greatly increased portability

- 6th edition of UNIX distributed in 1975. First version with widespread use outside AT&T.

History of Unix 2

- 7th edition distributed in 1978. Unix ported to VAX at AT&T, and to Interdata 8/32 and 7/32, and the IBM VM/370. This gave Unix a 32-bit address space (4GB).

- University of California, Berkeley -- BSD UNIX (Berkeley Software Distribution), TCP/IP. BSD 4.4 and later spinoffs (FreeBSD/NetBSD/OpenBSD) are free of AT&T code restrictions.

- AT&T SVR4 API spec, POSIX, XPG4

- Today there are many "flavors" of UNIX's with slight differences. Commercial versions (IRIX, Solaris, AIX, HPUX etc.) mostly derived from SVR4 codebase.

Linux/UNIX use at Dartmouth

- Interactive Use Systems

- Research Computing systems Andes, Polaris, Discovery cluster, RSTOR

- Private and departmental desktops and clusters (inc. Linux). Many Unix systems in Engineering, Computer Science and Physics.

- MAC/OS X is UNIXunder the hood (Mach/BSD Kernel with Apple GUI)

- Back-end Servers

- BlitzMail (but not new blitz) Library Catalogs and Databases

- Webster & Cobweb (development server)

- Administrative Computing, Oracle Databases, special purpose application servers: Remedy, Blackboard, CorpTime, License servers.

Linux/UNIX use around the world

- Many colleges and universities --- research, administrative, backend systems, scientific and engineering workstations.

- Major labs and research centers(CERN, Los Alamos ... )

- High Performance Computing HPC

- Wall street

Features of Unix

- Open, free or cheap

- Scalable and portable - Android phones, super computers, ATM, phone switches, real time embedded systems ...

- Multiuser, Multiprocessing, Preemptive multitasking

- Robust - Servers can often run for more than a year without rebooting.

Features of Unix 2

- Graphical desktop login, highly interactive software

- Command line logins, text-based programs, background programs, shell scripts

- Unattended programs, network daemons, cron jobs, mail filtering

- Networks and the Internet; Remote Access UNIX has many "built in" communication tools. Native networking is TCP/IP, but other protocols possible. Remote access was designed into the system from the start (with dial-in lines, even before the internet existed). Network services such as mail (smtp), http, ftp, usenet news, IRC, remote login, remote X display, remote printing, are all available.

How to get a Research Computing account

General Account

- Available to all 10-20GB of storage (mounts as a disk on PC/Mac).

- Fill out the online form: https://www.dartmouth.edu/~rc/account/research_computing_apply.php.

Discovery Cluster accounts

- Limited to faculty, staff and graduate students who need access to additional computing resources for their research. Coop membership model.

Logging in from a Macintosh or PC

There are many ways to talk to a Linux/UNIX machine. Terminal programs typically implement the secure shell (SSH) (telnet and remote login (rlogin) protocols are sometimes used but are not secure).

In addition to those, X server(X11, X) software provides the necessary control over the display that remote graphical software needs.

Logging in, usernames and passwords

- Will be using computers named Polaris or andes

- A username (user name) indentifies you and the password authorizes you

- Names to use today are rcomp1 , rcomp2, rcomp3 ... rcomp20

- One person to each username

- Password is ..... Note: Nothing will print when you type in your password--- just keep typing

- Logins fail due to incorrect usernames and passwords ... 99.999999$ of the time

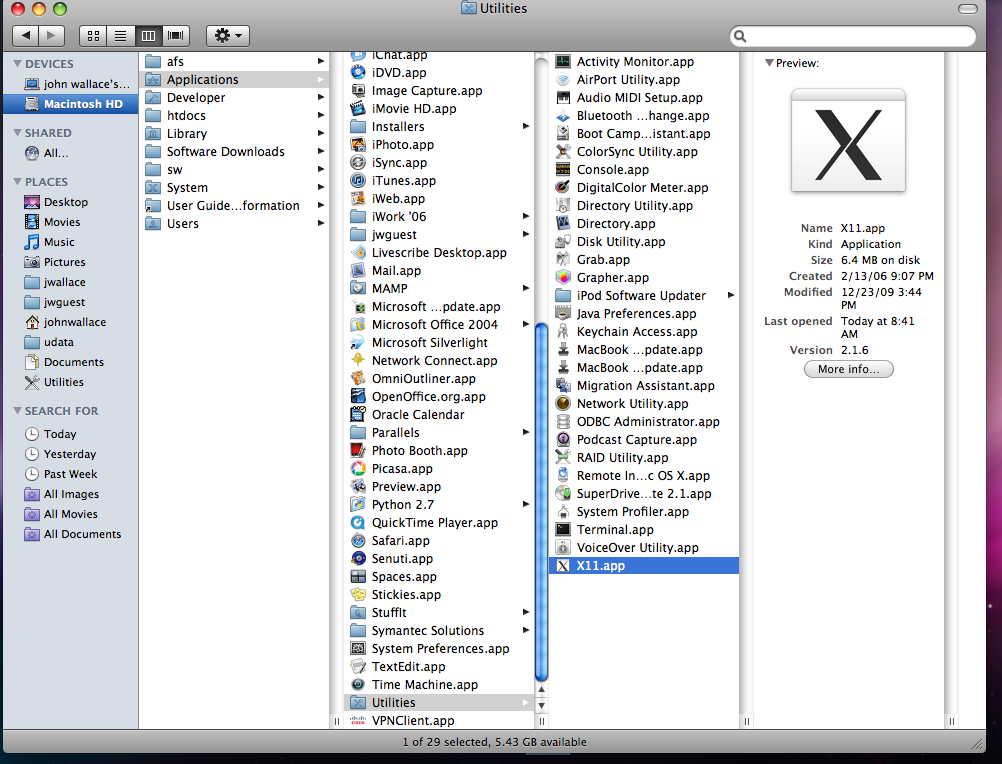

Mac X11

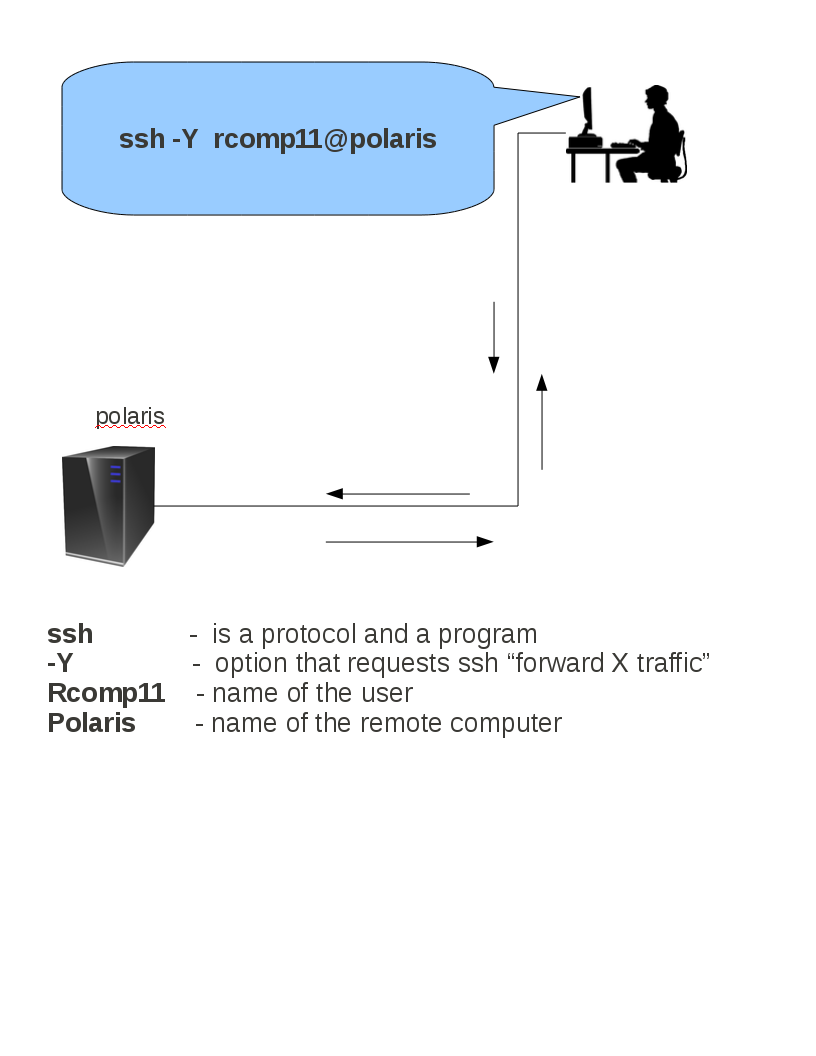

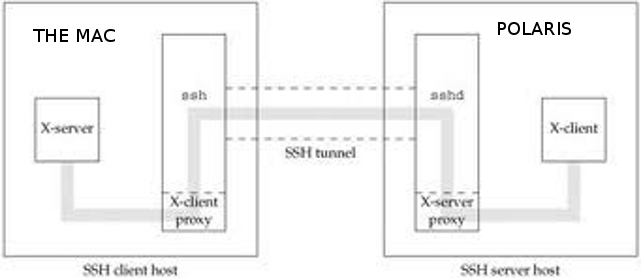

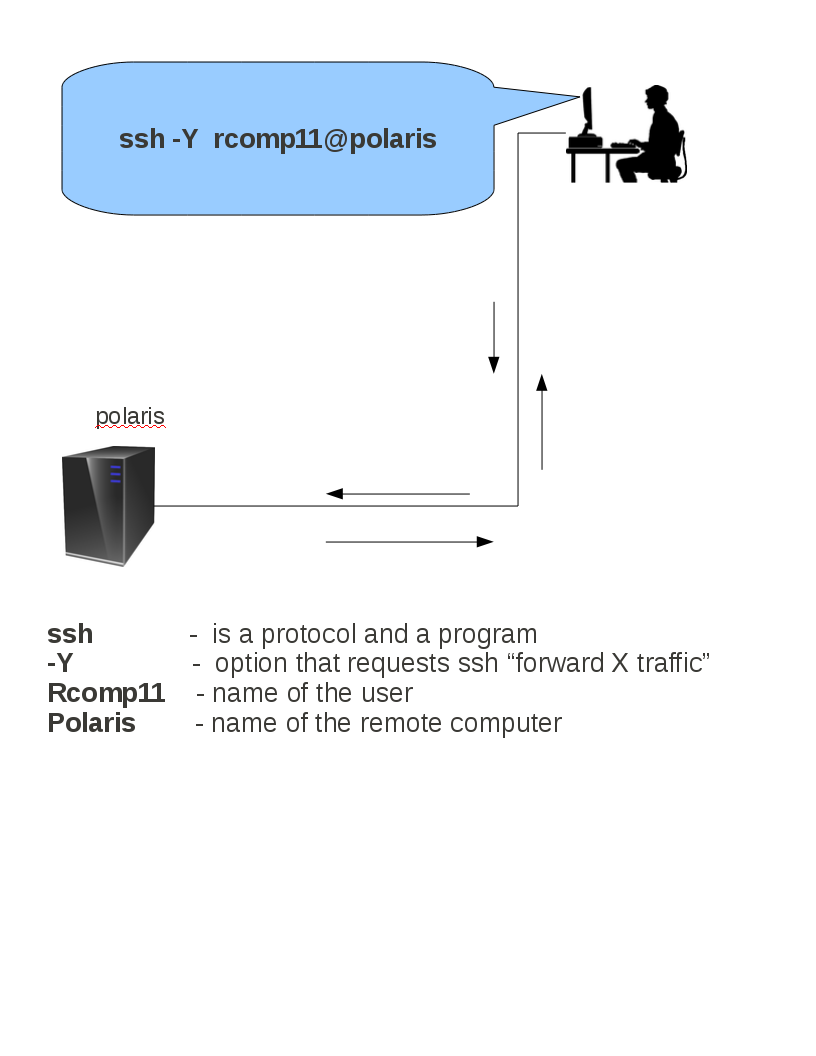

What is a ssh tunnel?

Easy way to do graphics (also protects the traffic, firewalls, encrypted ...)

Connecting (logging in, log on)

Logging in to UNIX

Where programs run; the login model.

- Three main environments for running programs

- Interactive session - X windows (GUI: local console or remote)

- Interactive session - command line (local console, or remote ssh session)

- Background operation (daemons, cron jobs, no user interaction)

- Command line (terminal) logins vs. X windows.

"X windows" is the standard graphical user interface for Unix. It is used on workstation consoles, and can be redirected to remote displays. Whether or not it can be used depends on the capabilities of the terminal ("terminal" means "whatever you are sitting at" - it may be a real terminal or a Mac or PC running terminal emulation software). X servers are available for MacOS and MS Windows. X windows is location independant - remote X windows programs run the same as local (console).

Logging in to UNIX (2)

Where programs run; the login model.

- Programs run on the Linux/UNIX machine and you see output on your terminal. The terminal may be remote (over the network), directly wired, or be the console device (workstations).

- When you log in with a command line session, a special program called a 'shell'

is run, commands that you type are processed by the shell. Most of this class concerns the command line

interface because:

- it is always available (often dial-in access is too slow for good X-windows display)

- it is scriptable and can be used to set up unattended jobs

- it is basis for the underlying tools run by the GUI, and the GUI menu configurations

- Certain Client-Server programs (Ex. Mathematica) can use a Mac/PC for display and UNIX for number crunching, remote execution.

Logging in to UNIX (3)

Where programs run; the login model.

- Displaying graphical output on the local console is generally faster than displaying remotely. Some graphical applications are coded in such a way as to make remote display almost impossible. Remote display to another Mac/UNIX/Linux workstation often works better than to a PC.

- Don't confuse the User Interface with the Operating System.

X windows provides the mechanism for graphical displays, but does not mandate any particular look and feel. There are many different graphical interfaces based on the X-windows core libraries; CDE, Gnome, KDE, ... . It may even be configured to look similar to MS Windows or MacOS. Similarly, there are various command line shells available which determine the look and feel of the text-based interface.

Getting Help

System error messages

foo: Command not found.

Probably the commonest error message you will see. Every command given to a Unix system, whether it is typed at a command line, read from a script, or generated by clicking an icon, actually tells Unix to find a program and run it. If the command is mistyped, or incorrectly installed, or your account tells the system to look in the wrong places, you will see this error message.

If you are getting a repeatable error message from any Unix command, and you mail us for help, try to include the exact error message (cut and paste it into a mail program if possible).

Getting Help (2)

Panic Buttons.

| logoff To stop a program To stop output When in doubt |

exit, ctrl-d,

logoutctrl-c'q', or quit (works on man pages, more, etc)'?' or help or 'h'

will sometimes bring up help.

|

Man pages, learning to fish

- Man pages: The 'man'(ual) pages provide in- depth

documentation of most of the systems features. There is also a database of man pages that you can search.

Type in

>

man-k process. Man pages have a standard format that we will look at. - Graphical user interface usually has online help available somewhere.

- Help: Typing the command "help" on some UNIX systems will bring up some form of help (non-standard)

- Application-specific help: Many applications, particularly those with X-windows interface, have extensive online help available within the program.

Man Pages solve problems

command name (man page section)

- Name

- Brief description of the command.

- Syntax

- This tells you how to invoke the command and includes command line options.

- Description

- Tells you more about the command.

- Options

- Explains the options that a command can accept.

Man Pages (2)

- Examples

- Shows you how to use the command, this can be one of the most useful sections if you find an example that does what you want.

- Files

- Tells you which files this command uses or depends on. Especially useful for system administrators types.

- Bugs/Warnings/Restrictions/Diagnostics ...

- This area can usually be ignored for simple invocations of commands but is the first place to look if you encounter problems.

- See also

- This is usually a list of related commands, or a list of a family of commands. Think of it as a primitive hyperlink.

Man page example

polaris:~>man whowho(1)

Name

who - print who and where users are logged inSyntax

who [who-file] [am i]Description .... Files

/etc/utmpSee Also

getuid(2), utmp(5)

Searching for man pages by keyword

rcomp2@andes:$ man -k internetrcomp2@andes:$ man psrcomp2@andes:$ man -k systemrcomp2@andes:$ man -k talk

1 .......... User commands.

2 .......... Programming interface (system calls).

3 .......... Programming interface (external functions and subroutines)

4 .......... File Format

5 .......... System (administrative) commands. Sometimes also (8)

+ .......... Other sections.

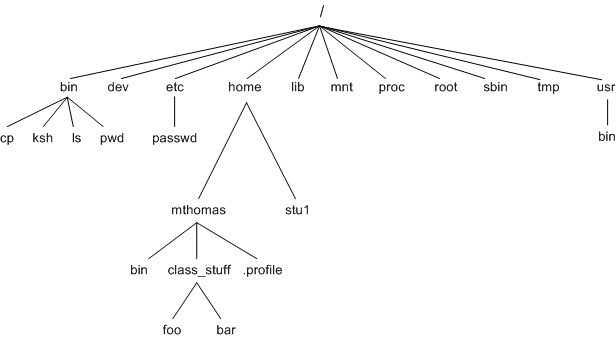

Storing Information -- The File System

- UNIX stores information in files. Files can be named almost anything.

- The file system structure (as seen by the user) is similar to the hierarchical DOS and Mac file system structure.

- The top file for the mac is the "desktop" file, for DOS/Windows it is the drive (C:,D: etc.) and for UNIX it's "/" which is usually called root.

- All disks etc. are attached (mounted) somewhere below the root. Users usually do not need to know or care which disk their files are actually on, only the mount point, which determines the full path name to a file.

- Everything in Unix is a file. Direct access to hardware (printers, tape drives etc.) and logical devices is made through special files. Most of these device interface files live in /dev.

- When you are logged on to UNIX you always have a location in the file system which is your current working directory. Filenames are assumed to be in this current working directory, unless some other directory is explicitly named. (More on this later)

-

>

ls - The

lscommand lists files in a directory, and various information about the files. You will use this a lot. ls -l- The

-lflag (long) lists most of the information stored about a file.

File Names

- Files and directories (and commands) are case sensitive.

- Files and directories (folders) can be named almost anything, as long as they do not contain "/" (since it has to separate directories in a path).

- In practice, many programs will get confused if filenames contain spaces and certain punctuation characters. Safe characters are [a-zA-Z0-9-_.]. Mixed case is allowed and all operations are case sensitive (unlike Mac and Windows).

- In particular, " and ' can be placed in filenames easily on Macs and then transferred to Unix - legal, but can cause headaches.

- Linux, no name limit. Macs and Windows have a 32-character limit. Macs and Windows preserve case for display, but internally treat upper and lower case as the same.

The UNIX file system (cont.)

The file system can be thought of as an upside down tree with "root" as the starting point.

The file system contains directories (folders) and files.

The UNIX file system (cont.)

Directories can contain other directories as well as files. A directory is just a special type of file, containing file names and pointers to the internal data structures which hold the permissions, ownership etc. for the file. Directories are manipulated using special utilities.

The UNIX file system (cont.)

File systems can be remote, actually attached to some other computer on the network. They can normally be treated just the same as local file systems, except they may be a bit slower. Research computing keeps all the user files on central servers (Rstor). Some Central Research machines keep local files in addition to using the remote file servers.

Most Unix systems can also mount disks with "foreign" file systems (e.g. MAC HFS, DOS FAT, NT, OS/2). Operations on such file systems are restricted to conform to the procedures of the foreign system (permissions, owner, filename limits)

Home Directories

- Every user on a UNIX machine has a home directory. This is always the initial working directory when you first log in.

- A home directory is owned by you (we will look at permissions later); a private work area.

- A home directory also has some special startup files that tell UNIX and the shell how to deal with you. For example your ".forward" file tells the UNIX mailer where to forward your mail. [.files are usually special in some way -- they are usually similar to stored user preferences]

Helpful hints

Use the history command to see what you have typed/done

Shows a list of commands that can then be recalled by using their number: Ex. $ !34

Use the Tab key for command and file name completion

The shell tries to figure out what you want to doUse the arrow keys to recall older commands

Command history in the tcsh: try pressing the arrow keys to recall previous commands and edit them before re-executing.Overview of Files & Directories

Look around

$ ls -l

What files and directories are in my current directory

$ tree

see a "tree" of directories look at the man page

Move around

$ cd ../

change directory ... to the parent

Find out where you are

$ pwd

Print working directory = where you are in the file system. Also in shell prompt

Looking around

$ tree -dA

Tree can do many things, show all the files that have recently changed, search for file names matching a string etc

$ ls

Lists the files in the current (working) directory.

$ ls path_name

E.g. ls /usr/local/bin

Lists the files in the named directory.

$ ls -al

Shows a "long" listing of the files. Include "hidden" files because -a was given.

$ ls -FR

Recursively lists all sub-directories and displays executable files with an appended "*" and directories with an appended "/".

Don't do this starting at the root directory!

Navigating Directories

Moving Around

$ pwdPrint working directory

$ cd[directory]Change Directory. With no argument, this changes the current directory back to your home directory. With a directory name, it tries to change directory to the named location, as long as it exists and you have permission to go there. The directory name can be an absolute or relative path (more on this later).

$ cd ~jwallaceShortcut to go to the home directory of jwallace.

Pathname Examples

Path name components are separated by "/". A path name can be relative or absolute. Relative path names start from the directory you are in and absolute path names start from "/".

Relative Paths$ cd ..

Shortcut to go to the parent directory (of the directory you are in) username.

$ cd ./

Shortcut to go to the current directory username.

$ cd ../../..

What is this?????

Absolute Paths

$ cd /afs/northstar/users/r/rcomp1

Absolute path to a home directory

$ cd /afs/worldwide/cern.ch

Absolute path to a cern cell

$ which rm

which command is being run; many times it will tell you the path

Working with Directories

$ tree

( see a "tree" of directories **look at the man page, can you make it look pretty? )

$ mkdir frog

(Makes a directory named "frog".)

$ mv frog toad

(Moves a directory, removes old directory (effectively a rename).)

$ cp -r toad lizard

(Copies one directory to another. The "-r" flag says to recursively copy files and subdirectories.)

Working with Directories (cont)

$ rmdir toad

(Removes a directory, if the directory is empty.)

$ rm -r toad

Will remove a directory even if it is not empty. Again, "-r" indicates recursive action, deleting all the contents first.

Use with caution.

Files: Copying, Moving and Deleting

$ cphow_many not_enoughCopies the first file to the second file, does not remove the first file.$ cp-r unix2 unix2copyCopies an entire directory. Creates a new directory.$ mvnot_enough bootyMoves file "not_enough" to file "booty". If the destination name is on the same device as the source, this is just a rename (and so it is very fast). For diffferent devices, amvis equivalent to acpfollowed byrm$ rmnot_enough bootyRemoves files "not_enough" and "booty". BEWARE of filenames with embedded spaces (see below). Tryrm -fon a file.$ ln -s lizard snakeLinks (similar to a Macintosh alias) one file to another. Think of it as creating a "pointer" to a file or directory; good for creating easy access to a shared resource. Take a look at this with a ls -l .. "lizard" is the real file, while "snake" is the alias for it.

lrwxrwxrwx 1 jwallace web 6 Oct 14 20:02 snake -> lizard

Files: Creating, Listing and Examining

Creating a file

-

$ echo" This is a test file" > test_file

- This creates a file using "echo" and "redirecting" the output to a file.

-

$ ls-a > ls_file

- This creates a file by taking the output(standard output) of the "ls" command and " redirecting" the output to a file.

$ ls -FR /people2 | wc > how_many

- This creates a file by taking the standard output of the "ls" command and "piping" it in to the "wc" (word count) command and then redirecting" the output to a file.

-

$ touchempty_file

- Creates a empty file! Useful way to signal an event.

Looking in files

$ more[file_name]

Will display the contents of a file one "page" at a time. Can also display the contents of a data "stream" one page at a time. Ex.$ ls -FR | more$ more /etc/passwd

The space bar will move you to the next page and the return key will move you down a line. A "q" will end the more (more can also search through a file see the man page).$cat/usr/man/cat1/cc.1

Streams the file to "standard output". What else can cat do??$head[file_name]Display the first few lines of a file$tail[file_name]. Display the last few lines of a file

Looking in files

Most of these utilities are intended for examining text files, with lines separated by "Newline" characters. Most files in Unix tend to be text files. The internal structure of binary files is application specific, and with the exception ofcat,

these utilities are not very useful with them.

Two utilities, strings and

od are very useful for examining binary files outside of their specific

applications.

Standard I/O and redirection

Most commands send their output to "standard output". The shell provides a mechanism for redirecting this to a file, or to another program. The default is to the terminal. Many programs also read some input (default is the keyboard of the terminal). Again, there is a mechanism to tell any program to read its input from a file or another program instead. > filename send output to the named file, creating it if needed. This is most common way new files are created>! filename

>> filename

< filename

prog1 | prog2

These facilities are available to all programs, but it is up to the individual programs whether they respect the conventions.

Unix Editors

UNIX editors are powerful tools but (sometimes) not very user friendly.-

viis the standard Unix text-mode (no X windows) editor. The main advantage of it is that it is always available on every system. It is powerful, but not the most intuitive to learn. -

neditis a good X windows editor, available on most platforms. It is similar in style to MacOS and Windows editors, but has many advanced features too. -

Emacsis the most powerful editor, great for programmers. It is extendible, uses X windows if available, but runs in text mode if needed. Integrates well with other gnu tools (e.g. gdb).Xemacsis a more GUIfied version of Emacs. Pull down menus for the most commonly use functions make it easier to learn. -

Joeandpicoare simpler editors (text mode only). Pico is the message composition editor used inside of the pine mail client, and to learn.

Unix Editors (cont)

vim is a vi-clone with many enhancements - sort of midway between

emacs and vi. It also uses X windows for additional GUI features if available, but can run in text mode.

Ex and

ed are also editors, best avoided. They are line-mode editors (as opposed

to full-screen text mode).

edit is often aliased

to "your favourite editor", but can be linked to ed on some systems.

Note that these are editors, not word processors or text formatters.

The login shell

- When you log in to a UNIX machine with a command line session, or open a terminal window in a graphical session, you get a shell. A shell takes commands that you type in decides what to do with them.

- There are many different shells available. Csh(C-shell), sh (Bourne shell), tcsh, kcsh, bash (bourne again shell) --- you can even write your own shell.

- Your login files (.cshrc .profile) set up some defaults when you log in. These defaults create an environment for you. This environment includes setting your search path so that common commands will work, setting the man page search path, setting the default printer, terminal type and more. You can customize these log in files for your environment.

- Shells have some nice features that every user can take advantage of: history, aliases etc.

The login shell

- The shell is also a programming language. The simplest of shell scripts is just a file containing commands as typed.

- Some commands are interpreted directly by the shell (internal commands), while for most of them, the shell will create a new process. All the internal commands are specific to the particular shell you are using.

- The login "shell" may be set to a custom application, not a general purpose shell (e.g. Webster, or the "newuser" login on some systems)

- Unattended background operations, e.g. >

cronor >atjobs still have a shell process to interpret the commands, even though there is no user interface.

More on shells

The Environment

The environment variables are a way to pass information to programs - any program can examine these strings and modify its behaviour (e.g. PRINTER is looked at by thelpr program. Some of these environment variables can be changed,

others are preset by the system.

$ env

HOME=/classes/rcomp1

SHELL=/usr/local/bin/tcsh

TERM=vt100

USER=rcomp1

PATH=/bin:/usr/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin/X11:/usr/ucb:.

HOSTTYPE=sun4

More on shells

VENDOR=sunOSTYPE=solaris

MACHTYPE=sparc

SHLVL=1

PWD=/classes/rcomp1

LOGNAME=rcomp1

GROUP=users

HOST=sunray.dartmouth.edu

MANPATH=/usr/local/man:/usr/man:/usr/share/man

PRINTER=berry-public

Shell commands

Command Line Arguments

The other way information is passed to applications is through the command line arguments. Everything following the program name on the command line, except things interpreted directly by the shell, is made available to the program. Typically these are option flags (to modify the behaviour of the program) and filenames (for the program to act on). The program may then also have a direct interaction with the use via a text or graphical interface. Most program use all of the methods.Many featuresof Unix are designed to help in automating procedures (Unix users are lazy). Passing information via the environment and the command line is scriptable, while direct interaction via the keyboard and mouse is not.

Job control

Shells also allow you to place jobs in the background and run multiple processes from one shell session, although multiple windows are easier for this.$ ls-FCR > save_it &The "&" says make this a background job.$ ^Zcontrol-Z sends a "suspend" signal to a currently running process$ bgcontinue execution of a suspended process in the background (must not try to read from the keyboard, but can write to the screen)$ & fgresume execution of a suspended program in the foreground$ & jobslist background jobs running in current shell session.

Shell commands

These commands are allcsh

tcsh internal commands, designed to make life easier

at the command line

$ source .cshrc[.login]Re-reads your log in files as if(almost) you had logged in again. Good for making changes to login files and testing them. Don't make changes to log in files and then log out and back in to test them. You might not be able to log back in.

$ !!Execute the last command again.$ !23Execute command number 23 again.$ aliasShows aliases. An alias is a command shortcut. Can make things much simpler and faster.$ alias his historyCreates an alias called "his" for the command "history".

Other UNIX commands

An assortment of other useful UNIX commands --- remember that many commands can be "joined" together with the pipe "|" and that output from a command can be sent to a file with the redirect symbol.Line oriented commands

-

grep - Searches a file for the string and reports on all matching lines.

-

find - Searches though a file system. E.g.

find /usr/share -name \*zip\*will search the filesystem below "/usr/share" for filenames with "zip" in them. -

sort - Sorts (alphabetic or numeric) lines in a file.

-

cut - Cuts fields out of a file.

Other UNIX commands

who

w

is almost identical to who

mail

at

script

Other UNIX commands

sed

awk

Other UNIX commands

Screen oriented commands

-

talk - Talk to another person on the internet.

-

irc - Internet relay chat. Talk with lots of people on the internet.

-

pine - A mail reader. There are other mail readers available too. You can even use a mail

program at the end of a pipe. E.g.

w | grep sam | mail $USER. This runs the "w" command and looks for user (string) sam; the output is then mailed to $USER (always set to your username). textblitz- A purely text-based interface to the Blitzmail system

-

top - Show the most active processes on the system. An animated, sorted,

pslisting.